Summary

A revealing walk through an ancient glaciated landscape.

You’ll know that Scotland was once covered by glaciers – in the ‘ice age’. But how do we know? What is the evidence the glaciers left behind? This short, self-guided walk (1.6mi/2.6km) along Glen Shee from the Spittal of Glenshee will introduce you to the abundant physical evidence and transport you back 20,000 years to a very different world.

Know the code before you go: Read the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.

Please use the arrows on left/right side to go to previous/next route.

Click here to download our booklet, From Deep Time To Our Time, Walking Across The Cateran Ecomuseum.

You can also listen to an audio version of each Points of Interest, spoken by Dr Richard Tipping.

With thanks to Dr Richard Tipping for creating the content for this itinerary.

Route Stats

Total Distance: 3 km

Total Ascent: 30 m

Terrain: Mostly flat on paths and pathless terrain

Route Category: Easy

Walking Time: 1 - 2 hrs

Start/Finish: Spittal of Glenshee

OS Grid Ref: NO 10948 70175

Nearest Parking: Car park at the start

Key Facilities on Route: None

OS Landranger Map: 53 (or custom Cateran Ecomuseum map)

For information on local accommodation & services click here

More Information

This route shows you some of the physical remains of the last glaciers along the Cateran Trail in Glen Shee. Almost everything you’ll see was shaped and formed by ice around 20,000 years ago and just after. The images we’ll show you are combined with modern-day examples from glaciated landscapes to help recreate what was once here not so long ago. We drop in links to websites where things are explained in greater detail but which won’t remind you of revision for exams.

You can listen to an audio track, introducing the walk and spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, who designed the walk for us.

Route Description

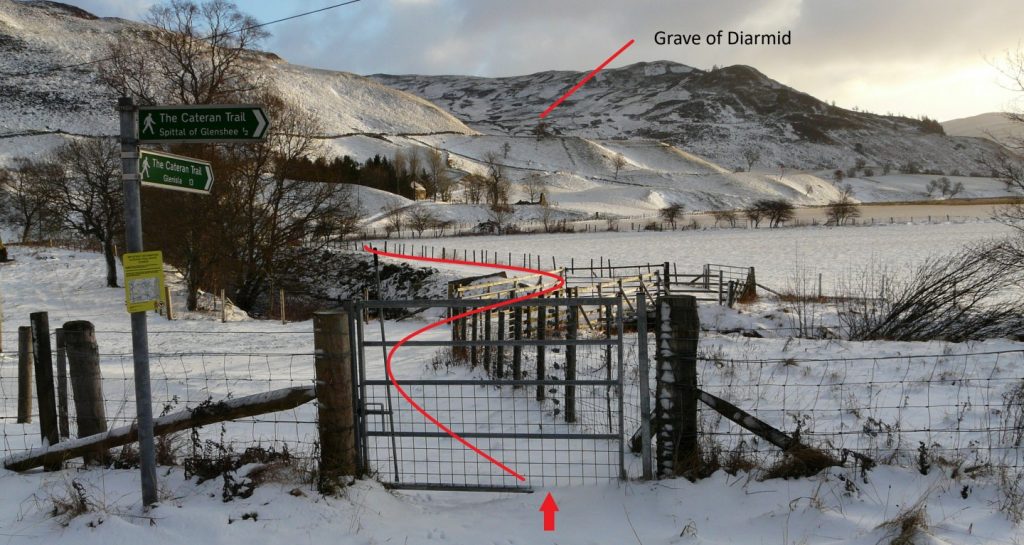

We start at the Spittal of Glenshee, where you can park, and walk down to the Grave of Diarmid, 0.75 miles (1.2 kilometres). The walk, in total is. It’ll take a couple of hours because there’s lots to see. At times we’ll lead you away from the Cateran Trail, but only by a couple of hundred metres or so, on grassland. Some farm tracks may be muddy. Walking boots should be fine. Take waterproofs–this is Scotland after all–and keep an eye on the weather.

Find out more about some of the key Points of Interest below.

Park on the road in front of Gulabin Lodge. Cross the A93 with care. Walk on the grass verge to a signpost on your right to the Cateran Trail. From here you can see the Grave of Diarmid and how short the walk is.

Cross the bridge over the river. Pause and look up Gleann Beag to your left.

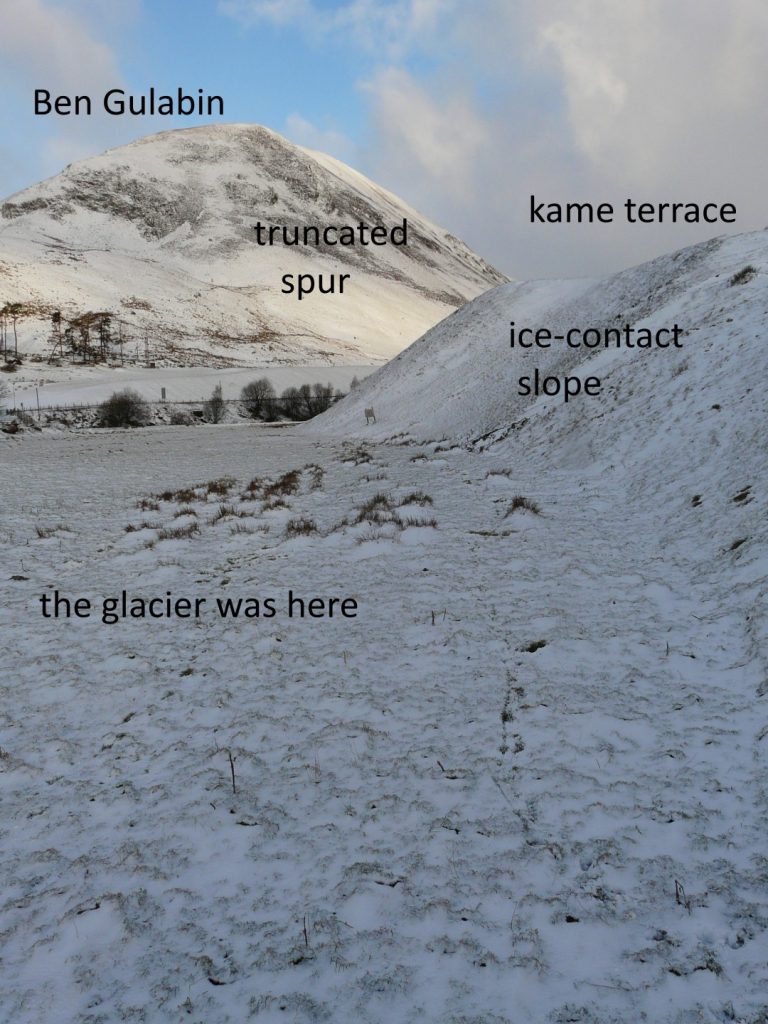

1. The A93 goes up Gleann Beag to the ski-centre at The Cairnwell and the high ground of The Mounth. The river you’re crossing is the Allt a’ Ghlinn Bhig. Look up Gleann Beag. The valley sides are smooth and straight and steep. They were shaped by glaciers 20,000 years ago that descended from The Mounth. These straightened the valley, streamlining and trimming the valley sides, and creating truncated spurs. The nearly vertical valley sides give rise to the U-shaped valleys beloved of Geography teachers.

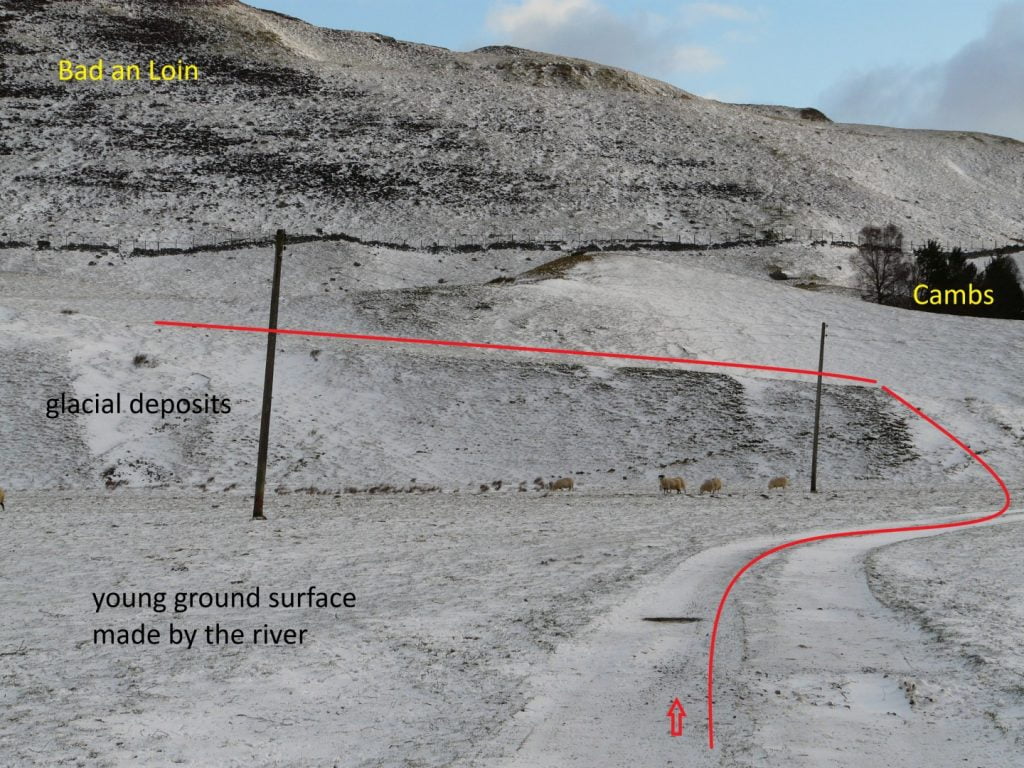

In Gleann Beag the truncated spurs rise to at least 550m above sea level on Bad an Loin, above Old Spittal Farm. With the valley floor at around 330m OD, we can say that the ice was at least 200m thick. In fact, all the peaks in Scotland were covered by ice 20 000 years ago, under 2-3km of ice.

Follow the farm track.

2. You’re walking on flat ground that is much younger than the last glaciers. It has been made by the river. Over many centuries, this land has also been farmed, smoothing out what the river left behind. But ahead of you is a steep bank of grass that will take you back in time to the last ‘ice age’. The bank itself has been formed by the river eroding it. The bank is older than the river.

You can listen to an audio track that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

Leave the Cateran Trail to your left before the small stand of trees at Cambs and choose a gentle slope to climb to the top of the bank.

3. On the way up there are lots of sheep-scrapes where sheep have exposed the materials forming the bank. These are loose, easily eroded sands, pebbles and boulders, rounded by being rolled in water. They are at least 20m thick.

4. You climb on to a surprisingly flat surface some 20m above the Cateran Trail and the river. This is called a terrace. It extends 150m to the base of Bad an Loin. It’s made of sand and gravel. This cannot have resisted the force of the glacier that sliced off the valley sides in Gleann Beag, so it’s either younger than the glacier or it formed at the same time.

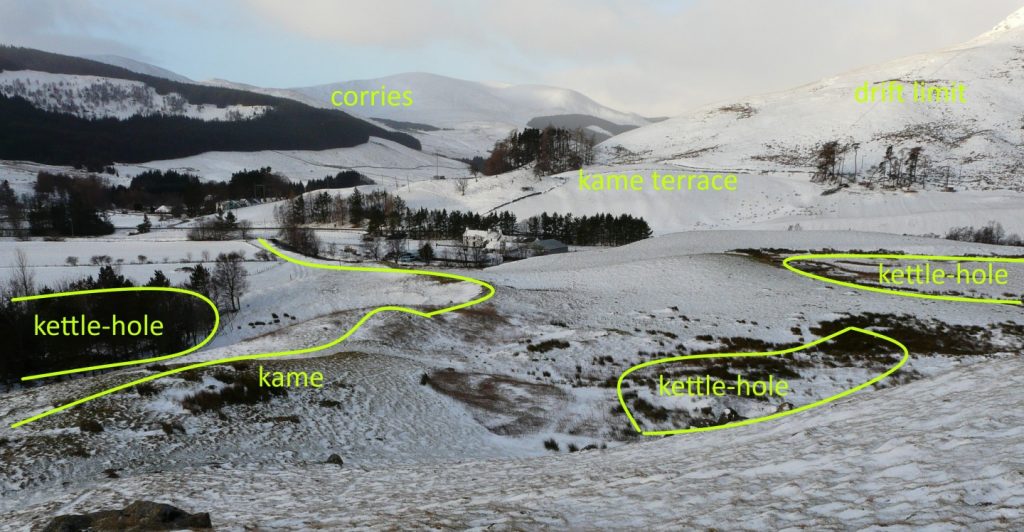

The sands and gravels were deposited by meltwater issuing from the glacier. Glaciers aren’t just ice: rivers and streams flow in tunnels under and inside the glacier. Sands and gravels come from the rocks the glacier has eroded. The terrace you’re on formed at the side of a glacier, between the glacier and the slope of Bad an Loin. This is a kame terrace. Kame or kaim is a Scottish word meaning a ‘comb’. Kames often form crests or ridges of gravel like the teeth of a comb. You’ll see these ridges on the edge of the terrace as you look around. The glacier was where you walked up.

The steep bank you climbed up from the valley floor is probably an ice-contact slope.

The kame terrace leaned against the glacier, which would have towered over you as the terrace rapidly built up. Torrents of meltwater moved the gravel around, making a flat surface. When the glacier melted, the surface was left high-&-dry.

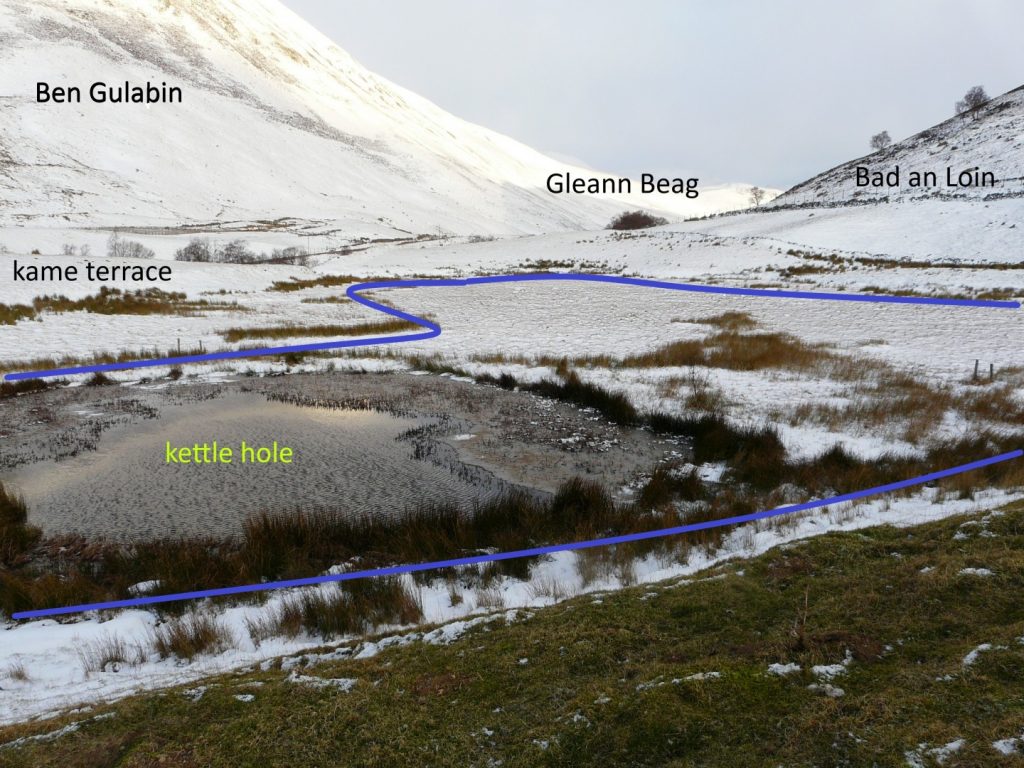

5. Towards Gleann Beag is a large pond on the kame terrace. It’s the last flooded remnant of a much larger pond, more than 100m long, now almost entirely infilled with peat. Yet there are no streams feeding the pond with water. How does well-drained sand and gravel support such a pond, so high above the valley floor? The pond is another glacial feature, called a kettle-hole. How did it form? Imagine the glacier where Old Spittal Farm is. When it melts, great chunks of ice can be left behind on the kame terrace. The chunk of ice then melts away. It leaves a hole in the kame terrace. Over time, clay from the glacier falls into the hole. This stops the water draining through the gravel terrace. The hole fills with water. Lake mud then forms, and finally peat. This infilling doesn’t happen with all kettle-holes. You’ll see several hollows on the route, big and small, that are kettle-holes, but which are dry because they didn’t trap clay.

You can listen to an audio track that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

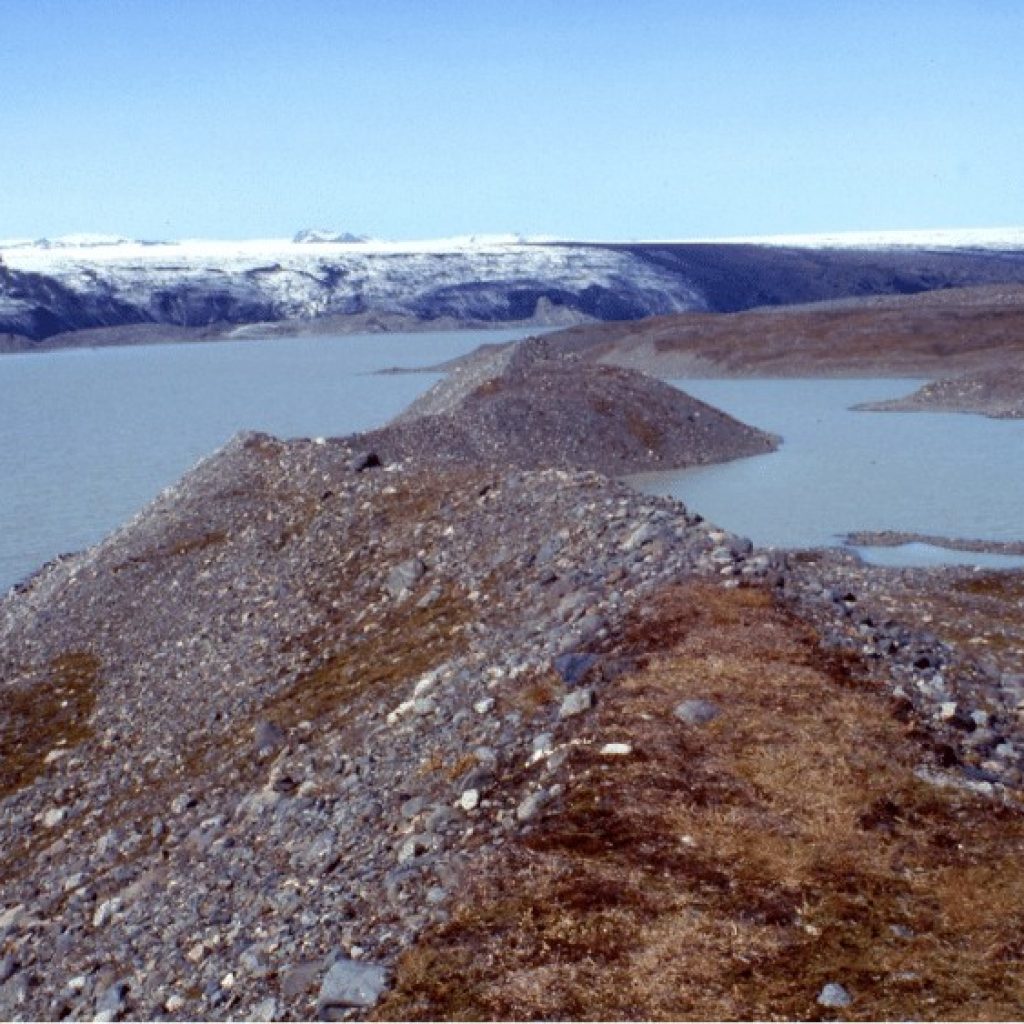

Where you are now 16 000 years ago.

Kettle-holes are enormously valuable because the earliest sediments retained in them should be close in time to the melting of the glacier. This photo could almost be what you could see here 16 000 years ago when the glaciers were retreating. Retreat or deglaciation was rapid. The Cairngorm, where all the ice in Glen Shee came from, was ice-free around 15 000 years ago.

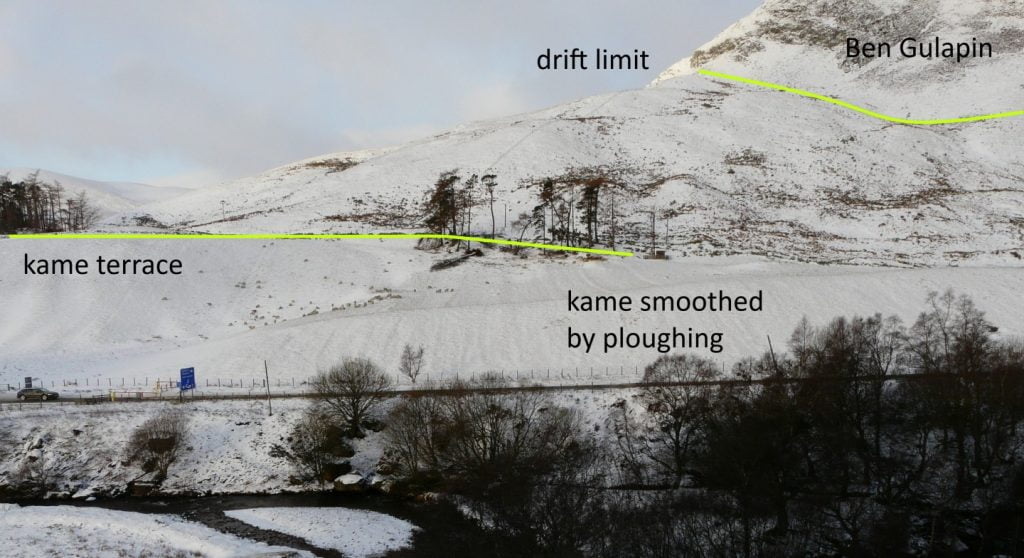

6. From the edge of the kame terrace above the river, look across to Ben Gulabin.

You’ll see another kame terrace, and one ploughed centuries ago. But above these you’ll see the lower slope pf Ben Gulabin has a lumpy appearance. This is glacial too. The lumps are called moraines, made of boulders and sand and clay all mixed up, formed under a glacier. The change from moraines to the rock above is called a drift limit. ‘Drift’ is an old term used by people who couldn’t explain how moraines were made, so they thought they had drifted in during Noah’s Flood. The drift limit marks where the glacier was – but the glacier was much thicker than the drift limit.

You can listen to an audio track that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

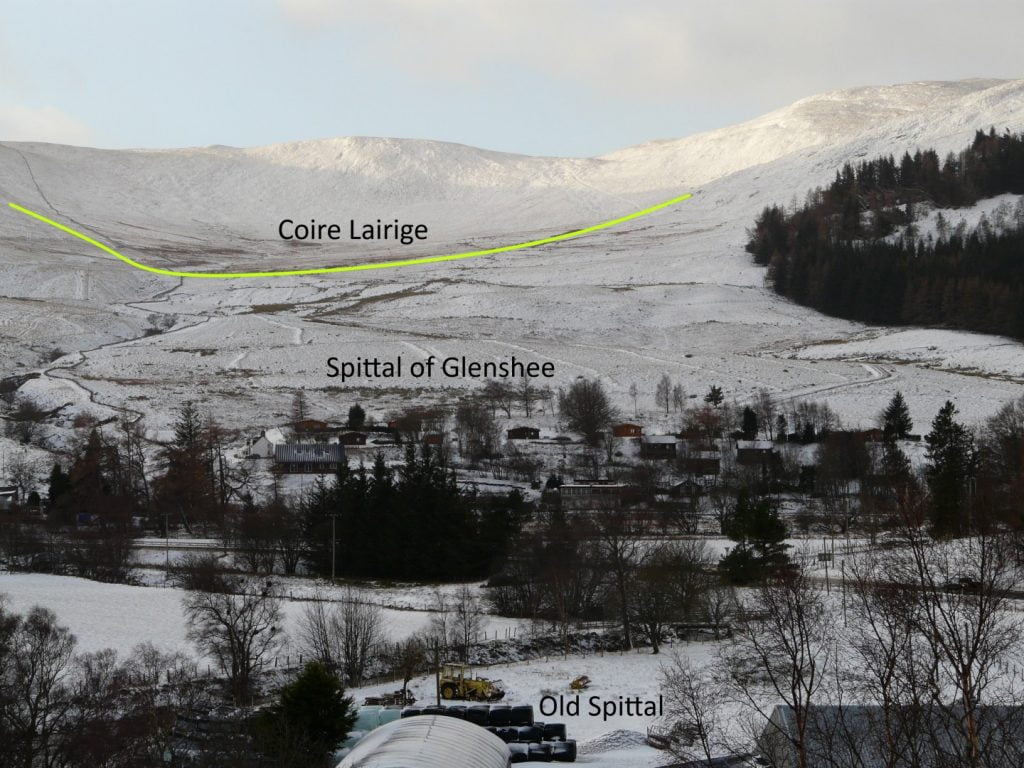

7. Look across Old Spittal Farm and the Spittal. On the far hillside is Coire Lairige – pronounced Corrie – a big bowl-shaped hollow in the mountain ridge. This, geologically, is called a corrie: we use the Scottish name, as with ‘kame’. These hollows are where ice ages begin and end, where ice first forms from snow blown onto north-facing slopes and where the ice lingers longest before deglaciation. To the right of Coire Lairige and the plantation, you might see two more, bigger and more impressive – Coire a’ Bhlarrain and Coire a’ Ghearraig.

You can listen to two audio tracks that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

To walk to the Grave of Diarmuid, stay up on the kame terrace at the base of Bad an Loin and through a gate in the wall ahead.

8. As you walk, you’ll see dry kettle-holes below you as well as the pond. You can trace one long kame, the comb-like ridges that cross the kame terrace fed by meltwater. The crest of the kame tells you which way the water flowed 16 000 years ago.

You can listen to an audio track that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

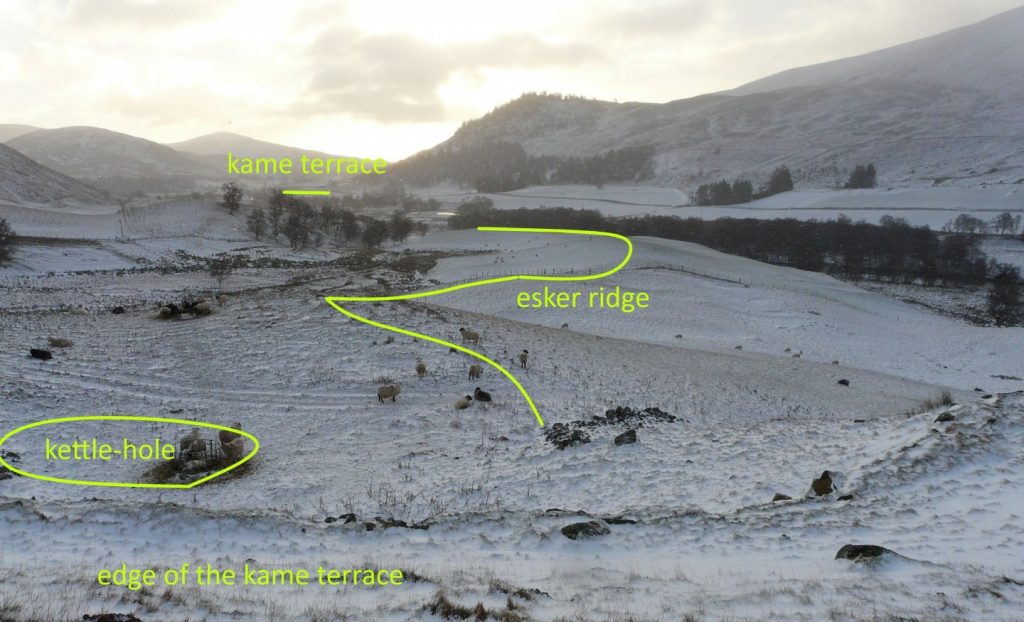

9. As you approach the Grave of Diarmuid, you’ll see that there is more than one kame terrace.

They’re at different heights above the valley floor. The highest surfaces are the oldest. Younger surfaces formed as the glacier shrank.

10. Grave of Diarmuid: The Grave is a later prehistoric monument, maybe 3,500 years old. These are called ‘4-posters’ for obvious reasons. The builders chose to place this monument on a natural mounded kame, perched a metre or two above a slightly younger kame terrace that formed as meltwater swirled around the knoll. The down-valley end of the Grave is stream-lined as the water shaped it. This is the highest and oldest kame terrace, the first to form, but beautifully preserved. The builders of the 4-poster must have wondered how such a flat surface came to be there. Before we realised, in the 1820s, that Scotland one had glaciers, so would we.

You can listen to an audio track that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

Looking down-valley from the edge of the kame terrace, you’ll see slightly younger glacial landforms, more kames and kettle-holes. And a glacial landform we’ve not seen before. This is a slender ridge running obliquely into the centre of the valley. It looks like the ridges we saw on the kame terrace. But it’s not surrounded by a kame terrace and it’s much bigger. This is an esker. Eskers form inside glaciers. Gravel flowing through subglacial meltwater channels can fill the tunnel. When the glacier melts, the tunnel is preserved as a ridge.

You can listen to two audio tracks that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

The esker you’re looking at was formed when the glacier had almost retreated up valley from here. From the orientation of the ridge, much of the gravel may have come from the kame terrace you’re on that was by then being eroded.

This esker can be traced out into the centre of the valley. It hasn’t been eroded by the river. Down the valley, you’ll start to make out flat-topped kame terraces and esker ridges above the valley floor. They are continuous along the glen. If you’re heading for Blairgowrie, you won’t stop seeing them now. They are only separated by a narrow slot made by the river. This shows how little has changed in this part of Gen Shee over the last 16,000 years.

Now head south east and look for a gentle slope to get to the farm track, which rises to meet you. This is the Cateran Trail to take you back to Old Spittal and the present day.

You can listen to an audio track that accompanies this section of the walk, spoken by palaeoenvironmentalist, Dr Richard Tipping, below.

All photos by Dr Richard Tipping except for the final one which is attributed to Clive Auton.

Points to visit

Along the way you will find these points of interest:

Diarmuid’s Tomb

One of many legends in Glenshee connected to Finn mac Cumhaill. Dhiarmaid or Diarmuid O’Duibne (“of the bright face”) was one of the legendary Finn mac Cumhaill’s most trusted warriors. It is said that he is buried in this mound and that...

Read more - "Diarmuid’s Tomb"